Healthcare attorney, Mary Holloway Richard published an article about the Sunshine Act in the May/June 2015 issue of the Oklahoma County Medical Society publication, The Bulletin.

CMS seeks to mitigate potential impact on prescribing and treatment practices

The Physicians Payments Sunshine Act (i) (“Sunshine Act”), despite its name, currently places no direct reporting requirements on physicians. Rather, the Sunshine Act requires that certain manufacturers of prescription drugs, biologic agents, medical devices and medical supplies (“Manufacturers”) and group purchasing organizations (“GPOs”) report to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) payments in specified amounts (ii) and other transfers of value to physicians (iii) and to teaching hospitals (iv). In addition, ownership and investment interests in applicable Manufacturers and GPOs held by physicians (and immediate family members) must be reported annually by applicable Manufacturers and GPOs. Covered payments include cash (or cash equivalent, in-kind items or services), stock (including stock options or ownership interest dividend profit or other return on investment), and other forms of payment to be determined in the future by CMS. While it is not the physician’s duty to report, the reporting requirement directly impacts physicians who receive such payments as their names appear on a list on the CMS website accessible by patients and other consumers (v).

The Physicians Payments Sunshine Act (i) (“Sunshine Act”), despite its name, currently places no direct reporting requirements on physicians. Rather, the Sunshine Act requires that certain manufacturers of prescription drugs, biologic agents, medical devices and medical supplies (“Manufacturers”) and group purchasing organizations (“GPOs”) report to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) payments in specified amounts (ii) and other transfers of value to physicians (iii) and to teaching hospitals (iv). In addition, ownership and investment interests in applicable Manufacturers and GPOs held by physicians (and immediate family members) must be reported annually by applicable Manufacturers and GPOs. Covered payments include cash (or cash equivalent, in-kind items or services), stock (including stock options or ownership interest dividend profit or other return on investment), and other forms of payment to be determined in the future by CMS. While it is not the physician’s duty to report, the reporting requirement directly impacts physicians who receive such payments as their names appear on a list on the CMS website accessible by patients and other consumers (v).

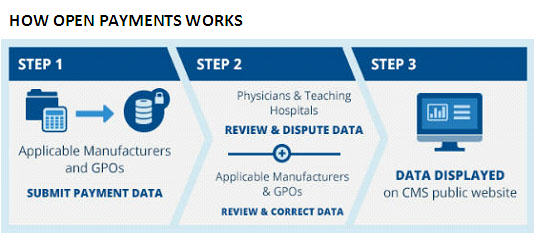

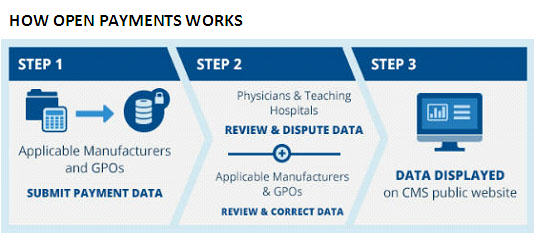

The purpose of the Sunshine Act is to identify potential biases in physician prescribing and treatment practices, to reveal conflicts of interest for clinical researchers and educators, and to identify transactions in which payments involving potential referrals by physicians exceed fair market value. The Sunshine Act creates the Open Payments Program for the actual reporting of the financial payments and transfers of value to physicians. Currently the burden is on the Manufacturers to report payments for consulting fees, contracted services, honoraria, gifts, entertainment, food, travel, education, research, charitable contributions, royalty or license, current or prospective ownership or investment interest, grants, direct compensation for serving as faculty or speaking at a medical education program, and any other nature of payment or transfer of value as defined by the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS.”) The form of the payment and the nature of the payment must be reported. See Table 1 below. Data has been collected since August, 2013, and is due to CMS by March 31 of each year. The first report was available to the public on September 30, 2014, and the 2014 report is predicted to be available on June 30, 2015 (vi).

The regulations provide for a formal dispute resolution process whereby physicians can seek to correct inaccurate information. In September, 2014, representatives of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies and organized medicine expressed concerns about the database and its presentation of data to the public in a potentially misleading manner. CMS shut down the Open Payments system for a period of time to address these issues. On October 30, 2014, CMS announced a procedure for Manufacturers and GPOs to report information not previously accepted by the system because of data errors, and CMS extended the reporting time accordingly. CMS has provided guides for Manufacturers to use to correct records and for covered recipients to correct information submitted in compliance with the regulations (vii).

Registration with CMS to receive notifications and information submitted by Manufacturers and GPOs is voluntary. This information is now available on the CMS website, to public and regulators alike, but the website itself continues to present issues of accuracy and ease of on-line accessibility. Physicians and teaching hospital representatives have the opportunity to review and, if appropriate, dispute information reported about them in the Open Payments System (viii).

Source: ttps://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/How-Open-Payments-Works.html

It has been necessary to resolve a number of procedural and substantive issues with the reporting requirements including initial confusion about the information that had to be reported and by whom. Example of substantive issues to be resolved may be helpful is understanding the regulatory climate. Some confusion has surrounded the CMS treatment of payments related to continuing medical education. “Direct payments” have always been included in the Sunshine Act’s reporting requirements. “Indirect payments” refers to payments by a manufacturer to a continuing education organization where the Manufacturer directs that the third party provide the payment or transfer to a covered recipient. In the October, 2014, final regulations, CMS responded to widespread criticism of its treatment of the CME by requiring reporting in 2017 payments (direct and indirect) made to continuing education organizations in 2016 as long as the speaker can be identified (ix). Further, payments to physicians for speaking at CME programs need not be reported if the following conditions are met:

- The CME program meets accreditation/certification standards of one of the following: (1) the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education; (2) the American Academy of Family Physicians ; (3) the American Dental Association’s Continuing Education Recognition Program; (4) the American Medical Association; (5) the American Osteopathic Association; and

- The Manufacturer or GPO does not pay the speaker directly; and

- The Manufacturer or GPO does not select the speaker or provide the third party, such as the CME vendor, with a distinct, identifiable set of individuals to be considered as speakers for the CME program (x).

Other frequent questions concern Manufacturers providing meals and other event support and sponsorships to physicians. In this context the Open Payments program is very specific–e.g., where a Manufacturer’s sales representative brings a meal to a staff meeting or a community education event for a number of persons, the cost of the meal is divided by the number of persons who actually eat the meal and this benefit is reported only if it exceeds $10.00 per person. This does not include meals eaten by support staff. Financial support of buffet meals at large-scale medical conferences is not reportable. The “User Guide” for Open Payments published by CMS is over 350 pages long and provides additional guidance to those reporting and those reviewing reports. It is accessible on-line (xi).

The Open Payments System is expected to significantly impact historic financial support of provider, patient and community education by industry. Importantly, these regulations and reporting requirements echo federal policy designed to avoid improper payments and incentives and market influence. These are the same concerns that spawned the expansion of federal antitrust, Stark and Anti-kickback law within health care.

Ms. Richard is a health care lawyer at Phillips Murrah, P.C. in Oklahoma City and was formerly in house counsel with INTEGRIS Health, Inc.

The Natures of Payment that are of Interest to CMS

| Nature of payment |

Definition |

Examples |

| Consulting fee |

Payments made to physicians for advice and expertise on a particular medical product or treatment, typically provided under a written agreement and in response to a particular business need. These payments often vary depending on the experience of the physician being consulted. |

Example 1: Company A has developed a drug to treat patients with a particular disease and wants advice from physicians on how to design a large study to test the drug on patients. Dr. J has a large number of patients with this disease and has experience doing research on how well medicines work for this condition. Company A asks Dr. J if he would spend about 10 hours per month to work with other physicians to create a new research study. Dr. J agrees and is paid for his time.Example 2: Company C has designed a new tool for surgeons to use when they are doing heart surgery. The company pays some physicians to give the new tool a “test drive” on a computer-simulated patient at the company headquarters. The physicians are paid an hourly fee for their time testing the tool and giving advice on how to make it work better. They are also paid for flights, hotel rooms and meals. |

| Compensation for services other than consulting, including serving as faculty or as a speaker at an event other than a continuing education program. |

Payments made to physicians for speaking, training, and education engagements that are not for continuing education. |

A physician who frequently prescribes a particular drug is invited by the company that makes that drug to talk about the medicine to other physicians at a local restaurant. The physician is paid for preparation time as well as the time spent giving the talk. |

| Honoraria |

Similar to consulting fees, but generally reserved for a one-time, short duration activity. Also distinguishable in that they are generally provided for services which custom prohibits a price from being set. |

A medical device manufacturer representative goes to a medical meeting and asks some physicians there for an hour of their time to talk about features they would like to see to improve a particular device. This representative pays each physician a one-time honorarium. |

Footnotes:

(i) The Physician Payment Sunshine Act is Section 6002 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C.§18001. The regulations can be found at: http://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Downloads/Affordable-Care-Act-Section-6002-Final-Rule.pdf.

(ii) There are specific reporting thresholds for applicable manufacturers and GPOs. The Open Payments reporting thresholds are adjusted based on the consumer price index. This means that for 2015 (January 1 – December 31), if a payment or other transfer of value is less than $10.21 ($10.00 for 2013, $10.18 for 2014), unless the aggregate amount transferred to, requested by, or designated on behalf of a physician or teaching hospital exceeds $102.07 in a calendar year ($100.00 for 2013, $101.75 for 2014), it is excluded from the reporting requirements under Open Payments. http://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/Program-Participants/Applicable-Manufacturers-and-GPOs/Data-Collection.html.

(iii) This law applies to physicians and other providers, but, for the purposes of this article, we will only reference physicians. The other providers as defined in Section 1861(r) of the Social Security Act to whom this law applies include medical and osteopathic physicians, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists and chiropractors. Providers exempted include medical and osteopathic residents, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and allied health practitioners. However, in some circumstances, payments to these types of providers may be imputed to physicians, thereby triggering the Manufacturers’ obligations to report payments.

(iv) Manufacturers and GPOs may also be referred to in this paper as “covered recipients.”

(v) https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/.

(vi) http://www.cms.gov/OpenPayments/About/Resources.html

(vii) The American Medical Association offers a toolkit for physicians to use in reviewing and dispute reports at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/advocacy/topics/sunshine-act-and-physician-financial-transparency-reports/sunshine-act-toolkit.page?

(viii) See Flow Chart 1 in content.

(ix) 42 C.F.R. §403.902.

(x) 42 C.F.R. §403.904(g).

(xi) www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/National-Physician-Payment-Transparenct-Program/Download/Open-Payments-User-Guide-%5BJuly-2014%5D.pdf.

Wellness is in the news again. Large employers have inserted wellness protocols and metrics into the workplace with great enthusiasm. Advertisements for webinars tout the importance of clinicians and counsel getting on the wellness bandwagon, and articles on the topic appear daily in local and national newspapers.

Wellness is in the news again. Large employers have inserted wellness protocols and metrics into the workplace with great enthusiasm. Advertisements for webinars tout the importance of clinicians and counsel getting on the wellness bandwagon, and articles on the topic appear daily in local and national newspapers.

The Physicians Payments Sunshine Act (i) (“Sunshine Act”), despite its name, currently places no direct reporting requirements on physicians. Rather, the Sunshine Act requires that certain manufacturers of prescription drugs, biologic agents, medical devices and medical supplies (“Manufacturers”) and group purchasing organizations (“GPOs”) report to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) payments in specified amounts (ii) and other transfers of value to physicians (iii) and to teaching hospitals (iv). In addition, ownership and investment interests in applicable Manufacturers and GPOs held by physicians (and immediate family members) must be reported annually by applicable Manufacturers and GPOs. Covered payments include cash (or cash equivalent, in-kind items or services), stock (including stock options or ownership interest dividend profit or other return on investment), and other forms of payment to be determined in the future by CMS. While it is not the physician’s duty to report, the reporting requirement directly impacts physicians who receive such payments as their names appear on a list on the CMS website accessible by patients and other consumers (v).

The Physicians Payments Sunshine Act (i) (“Sunshine Act”), despite its name, currently places no direct reporting requirements on physicians. Rather, the Sunshine Act requires that certain manufacturers of prescription drugs, biologic agents, medical devices and medical supplies (“Manufacturers”) and group purchasing organizations (“GPOs”) report to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) payments in specified amounts (ii) and other transfers of value to physicians (iii) and to teaching hospitals (iv). In addition, ownership and investment interests in applicable Manufacturers and GPOs held by physicians (and immediate family members) must be reported annually by applicable Manufacturers and GPOs. Covered payments include cash (or cash equivalent, in-kind items or services), stock (including stock options or ownership interest dividend profit or other return on investment), and other forms of payment to be determined in the future by CMS. While it is not the physician’s duty to report, the reporting requirement directly impacts physicians who receive such payments as their names appear on a list on the CMS website accessible by patients and other consumers (v).